Mathematics is made tangible for the child through the senses and movement.

When the child enters the Children’s House at three, the child’s mathematical mind is concrete and, with time and experience, it passes into abstraction. Dr. Montessori found that through concrete representation of an abstract idea, the child understands. She developed a collection of “materialized abstractions” to help the child know quantity and measurement; to compare, differentiate, find patterns and perform the four operations of arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

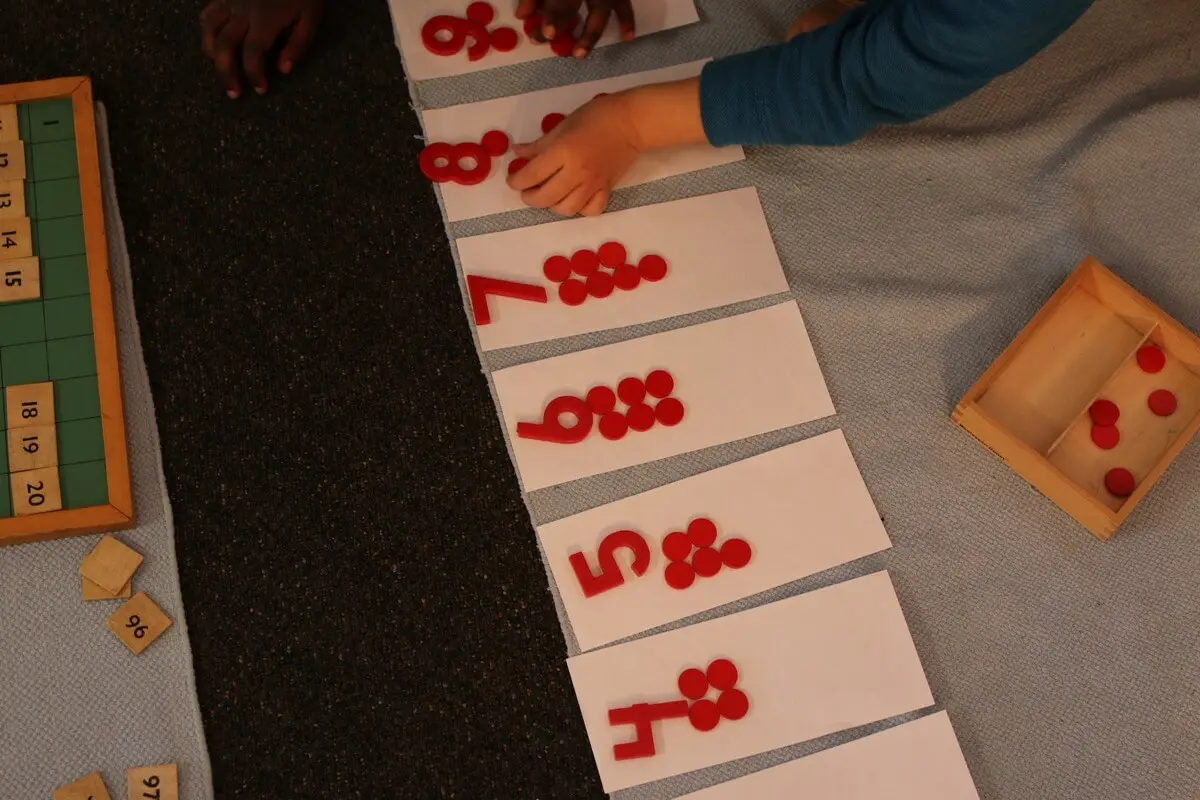

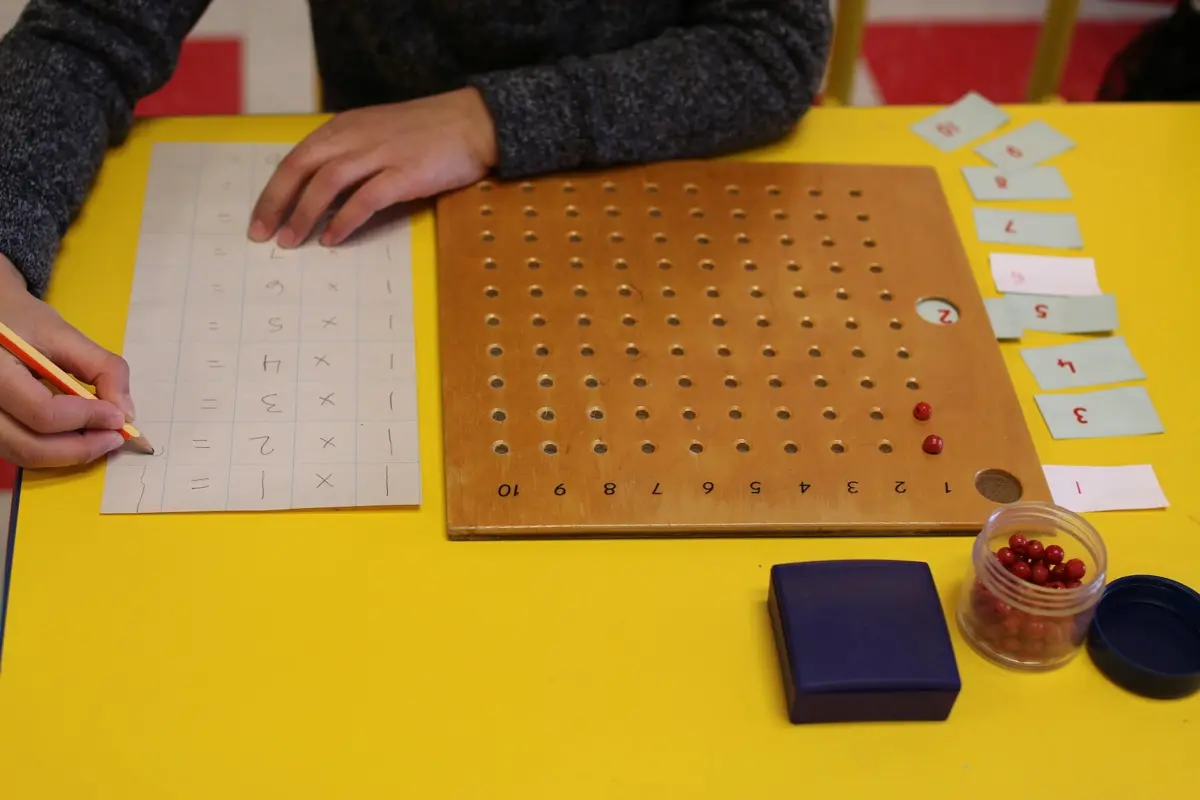

Mathematics is made tangible for the child through the senses and movement. Number rods and golden bead material give the child a sensorial impression of quantity and arithmetic. The goal is not so much if the child has added correctly; rather, the idea is for the child to “experience” mathematics. To understand with his senses and whole body movement what it means to add, to take away (subtraction), to add the same number many times (multiplication) and to share evenly among friends (division). The child holds and manipulates quantities, walks with the rod of five, counts the beads of the ten bar with the touch of her fingertips, exchanges squares of hundreds for cubes of thousands. She plays games with her friends in remembering a quantity and bringing objects to show for it. Rather than reading about Sally who had 100 pies and gave 20 to Robbie, the child acts out operations with the golden bead material and cards. In addition, because the child is working with concrete objects alongside the numerical symbol, quantity and its symbol unite and the child understands, for example, what “100” really means.

In all this work is the underlying respect for each child’s time in understanding mathematical concepts. To move from concrete to abstract thought is within the child’s own timetable. She cannot be pushed. The child is given the freedom to work with a piece of material as often as she likes for as long as she likes.